Computer vision tools are becoming increasingly common in human-subject research, with applications ranging from gait analysis to language acquisition. As these technologies move into sensitive domains, investigators have a responsibility to ensure that the software itself provides strong protections for privacy, fairness, and participant safety. This article emphasizes practical technology choices rather than regulatory process, highlighting features such as privacy-focused system design, encryption, controlled data retention, fairness monitoring, audit trails, and options for human oversight. Case examples illustrate the risks of biometric identifiability in gait analysis and the variability of speech recognition performance, as well as the broader challenge of addressing fairness without undermining confidentiality. By treating these safeguards as essential elements of research software rather than optional enhancements, investigators can build studies that both complement IRB protocols and advance human-centered computer vision in a responsible and ethical way.

Computer vision has moved beyond laboratory research into widespread use across healthcare, behavioral science, rehabilitation, and education. Systems that once served only exploratory purposes now influence real-world settings, capturing gait for fall-risk prediction, monitoring language development in children, or analyzing behavior in classrooms. This expansion brings with it a heightened ethical burden. Unlike survey data or lab assays, visual and audio data are inherently identifiable and resistant to de-identification. For early-career investigators, the challenge is not only securing IRB approval, but also ensuring that the software environment itself is aligned with participant protection.

NIH guidance stresses that responsible AI requires fairness, transparency, and bias mitigation, in addition to conventional privacy protections [1,2]. The risk is not abstract. Without encryption, video breaches can expose individuals in sensitive contexts. Without fairness monitoring, algorithms may misinterpret speech or movement in ways that stigmatize participants or undermine scientific validity. Without auditability, investigators cannot demonstrate compliance or reproducibility. This article argues that software safeguards should be considered as ethical design features, as integral to protecting participants as consent forms or retention policies.

Privacy-by-design is not an optional feature but the cornerstone of ethical CV research. In practice, this means structuring data pipelines so that privacy is embedded into the architecture itself. On-premises deployment remains the preferred approach, since institutionally managed servers limit uncontrolled external access. When cloud systems are necessary, investigators must verify that platforms meet HIPAA or equivalent standards and have explicit institutional approval.

Encryption both in transit and at rest is a baseline requirement, but it is not sufficient alone. Systems should automate retention policies, permanently deleting raw recordings after analysis while preserving only de-identified or derived data. This ensures alignment with NIH’s expectations for data minimization and secure handling [1]. Consent processes are strengthened when software can operationalize deletion, because investigators can make withdrawal guarantees enforceable rather than aspirational. In CV studies, where participants often underestimate the identifiability of their data, privacy-by-design architectures help bridge the gap between consent language and actual protections.

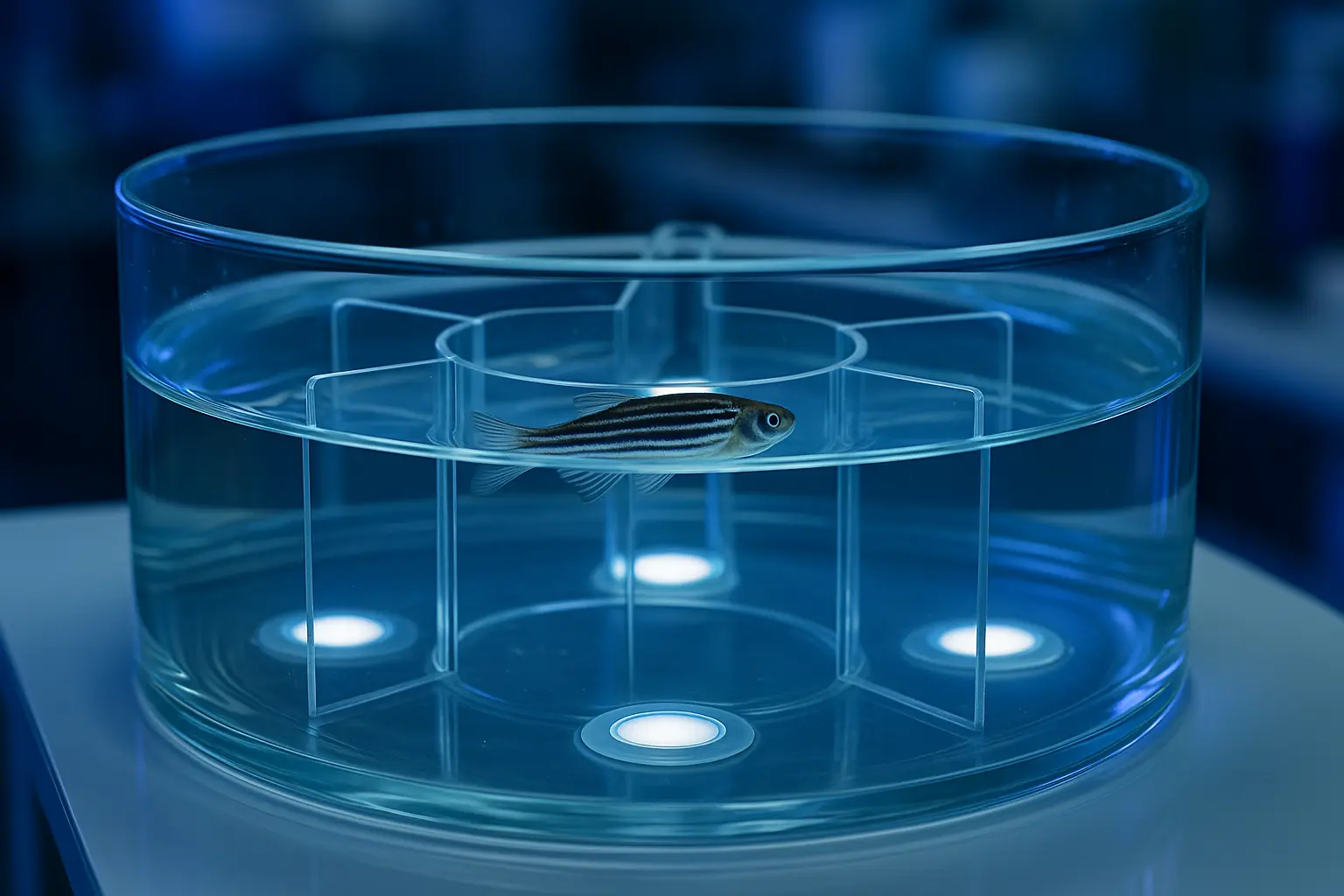

Gait analysis is a rapidly growing application of CV in healthcare and rehabilitation, offering insights into mobility, neurology, and physical recovery. Yet gait is more than a clinical parameter; it is a biometric marker. Research shows that gait patterns can uniquely identify individuals, even in the absence of facial features [3]. LIDAR-based recognition systems further illustrate the privacy implications, as they can capture detailed movement signatures without overt identifiers [4].

These characteristics make gait analysis particularly sensitive. A misclassified gait assessment could label a healthy participant as at high fall risk, potentially influencing care decisions or personal self-perception. Investigators should demand software that validates performance across diverse populations, including different body types, mobility aids, and health conditions. Systems should also allow manual review of borderline classifications to prevent overreliance on automated output. Automated deletion of raw gait recordings after feature extraction minimizes exposure while still enabling scientific analysis. Consent forms should explicitly note that gait is identifiable and subject to the same protections as more obvious biometric features.

Language acquisition studies present another high-risk domain. Speech and language data are deeply personal, difficult to anonymize, and highly sensitive in pediatric populations. Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) systems are known to vary significantly in accuracy depending on accent, developmental stage, and speaking conditions [5,6]. For instance, younger children may produce speech that falls outside model training distributions, resulting in higher error rates.

Responsible platforms should disclose benchmark performance across different conditions and allow investigators to quantify disparities in recognition accuracy. Linking datasets to consent records is essential, ensuring that withdrawal requests can be operationalized at the level of individual voice recordings. NIH policies stress that transparency and fairness must extend across diverse participant groups [2]. In language studies, failure to account for performance variability risks misrepresenting developmental milestones or producing inequitable outcomes in educational interventions.

Fairness is one of the most pressing challenges in CV research. Unlike physical risks, which are usually minimal, algorithmic harms can be systemic and enduring. Limiting data collection to protect privacy can reduce diversity in training datasets, exacerbating bias. Conversely, overcollecting data may strengthen fairness but heighten identifiability risks. Navigating this tension requires technical support from the software itself.

Platforms should integrate fairness monitoring tools that report performance metrics stratified by variables such as age, accent, or health status. Automated alerts when error rates exceed thresholds allow investigators to take corrective action during study design rather than post hoc. NIH policy emphasizes that equitable AI requires transparency at every stage [2]. Importantly, fairness is not only a technical issue but also an ethical one. A CV system that consistently underperforms for certain populations risks reinforcing inequities and undermines the beneficence principle in human-subject research [7]. Bias detection alone is not sufficient; investigators must also describe mitigation strategies. These may include rebalancing datasets, implementing fairness-aware algorithms, or introducing human-in-the-loop oversight for ambiguous cases. By embedding fairness checks directly into the software pipeline, platforms reduce the likelihood that bias will go unnoticed until after harm occurs.

Ethical research requires not only secure systems, but also transparent and verifiable processes. Audit logs provide an immutable record of every instance of data access, export, or modification. Such logs are critical during continuing IRB review, when investigators must demonstrate that only authorized personnel accessed sensitive data. Without these features, investigators must rely on self-reporting, which is more prone to error and less reassuring to oversight bodies.

Version control is equally important. CV research often involves iterative model development, and untracked updates to algorithms or datasets can alter a study’s risk profile. A system that documents dataset lineage, algorithmic changes, and analysis workflows supports both reproducibility and compliance. These practices echo frameworks for fairness, accountability, transparency, and ethics in AI [8]. They also serve participants by ensuring that their data are not subjected to unmonitored uses beyond the original scope of consent.

The software environment in CV research is more than a technical backdrop; it is an ethical infrastructure. Systems that embed privacy-by-design, enforce auditability, provide fairness monitoring, and adapt to domain-specific risks reduce participant exposure and simplify IRB review. Conversely, software that lacks these features forces investigators to manually compensate, introducing inconsistencies and vulnerabilities.

NIH guidance calls for AI that is not only innovative but also transparent, fair, and accountable [1,2]. When investigators treat software selection as part of their ethical duty, they reinforce participant autonomy, minimize risk, and enhance trust. By elevating software safeguards to the same level as consent forms or recruitment strategies, early-career researchers can build protocols that satisfy regulators while respecting the dignity of participants.

As computer vision research expands into gait analysis, language acquisition, and other human-centered domains, the ethical responsibility of investigators extends beyond IRB protocols to the software itself. Systems that incorporate privacy-by-design, transparency, fairness monitoring, and tailored protections are core safeguards for human subjects. Embedding these protections at the software level ensures that IRB protocols can focus on articulating protections rather than compensating for technical deficiencies.

Ultimately, ethical CV research requires more than compliance; it requires foresight. By integrating safeguards directly into the technological foundation of their studies, investigators can advance innovation responsibly, fostering participant trust while upholding the highest standards of fairness and privacy.

Written by researchers, for researchers — powered by Conduct Science.

Is a transitional year resident physician pursuing a career in diagnostic neuroradiology with a background in biochemistry. She is the founder of a collaborative initiative focused on radiology, artificial intelligence, and deep learning, connecting students and physicians through shared opportunities, interdisciplinary research, and mentorship. Beyond her research, she explores the integration of creative technologies such as virtual reality and 3D modeling into medical education and clinical practice. A VR enthusiast and artist, she believes that creativity and compassion should remain at the heart of patient care.