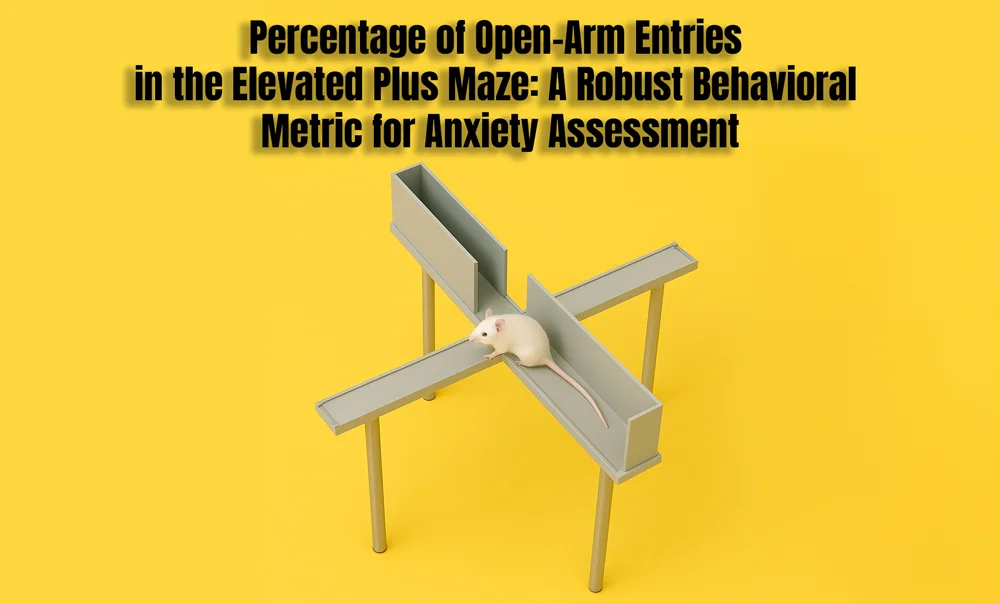

In the field of behavioral neuroscience, the Elevated Plus Maze (EPM) remains a cornerstone assay for investigating anxiety-like behaviors in rodents. Among the array of behavioral metrics used to interpret responses in this apparatus, Percentage of Open-Arm Entries is particularly significant. It reflects not only a subject’s willingness to explore aversive environments but also offers key insights into decision-making under anxiety-provoking conditions.

At Conduct Science, we are committed to supporting robust, reproducible research. In this article, we examine the foundations, utility, and nuanced interpretation of open-arm entry percentage—a parameter central to the evaluation of both basal and pharmacologically-modified anxiety states.

The Percentage of Open-Arm Entries is defined by the ratio:

Here:

This metric provides a normalized measure of exploratory preference, independent of total locomotor activity, making it a more reliable indicator of anxiety-like behavior than raw entry counts alone. This reliability is particularly critical when comparing treatment groups with potentially different baseline levels of activity.

The Elevated Plus Maze consists of four arms arranged in a plus shape: two enclosed by high walls (closed arms) and two open to the environment (open arms), elevated approximately 50 cm above the ground. Rodents naturally avoid open spaces due to their vulnerability to predation. However, their innate drive to explore competes with this avoidance, creating a scenario of conflict that is highly informative in behavioral studies.

This approach-avoidance conflict is what makes the EPM such a powerful tool for anxiety research. Behavioral choices made in the EPM reflect an animal’s internal state and provide quantifiable data that correlates with neurochemical and pharmacological influences.

While time spent in open arms is a well-established indicator of anxiety, percentage of entries offers a different but complementary dimension:

Unlike absolute open-arm entries, this ratio controls for differences in overall activity levels. It offers a normalized perspective, allowing researchers to distinguish between exploratory behavior and hyperactivity or sedation.

An animal that enters open arms more frequently in proportion to its total movement shows greater risk tolerance, often interpreted as reduced anxiety.

Pharmacological agents like benzodiazepines increase this percentage, while stress-inducing treatments reduce it (Lister, 1987).

This measure is consistent in both mice and rats, and across various genetic backgrounds, enhancing its translational value.

To ensure accurate and reproducible results, Conduct Science emphasizes the following best practices:

Only count an entry when all four paws enter an arm. Partial entries (e.g., head dips) are excluded to maintain consistency.

Use a 5 to 10-minute testing period, ensuring sufficient time for exploratory behavior without inducing habituation or fatigue.

Always analyze total entries alongside open-arm percentages. If a treatment reduces both, the effect might be due to sedation or motor impairment, not anxiety.

Minimize prior stress through gentle handling and consistent testing conditions. Rodents subjected to prior stress may show suppressed exploration and altered baseline percentages (Hurst & West, 2010).

Lighting, maze material, olfactory cues, and ambient noise all influence exploration. Standardization of these elements is crucial to reproducibility.

While the Percentage of Open-Arm Entries is highly informative, it is not without limitations:

Researchers are encouraged to use this metric in conjunction with other variables such as:

Using a multivariate approach enhances validity and helps dissociate anxiety-specific effects from general behavioral shifts.

The strength of this metric lies in its predictive and construct validity. Compounds that increase open-arm entry percentages in rodents often translate into anxiolytic effects in human trials. Moreover, by focusing on risk assessment behavior, the measure mirrors real-world decision-making processes involved in human anxiety.

This makes the Percentage of Open-Arm Entries not just a metric of interest, but a translational bridge between animal models and human psychopathology. It allows researchers to test hypotheses about fear, cognition, and pharmacological intervention in an ethically responsible and scientifically validated manner.

At Conduct Science, we understand that behind every behavioral metric lies a deeper neurobiological story. The Percentage of Open-Arm Entries captures a rodent’s willingness to engage with risk—a fundamental aspect of anxiety. When analyzed in the right context, this measure adds rigor, depth, and translational power to your behavioral studies.

As neuroscience continues to evolve, this classic yet powerful metric remains a vital part of the EPM toolkit—trusted by neuroscientists, pharmacologists, and behavioral researchers around the world.

Dr Louise Corscadden acts as Conduct Science’s Director of Science and Development and Academic Technology Transfer. Her background is in genetics, microbiology, neuroscience, and climate chemistry.