- Name: Sarah Ellen Rosenbaum

- Number of lab members or colleagues (excluding PI): 8

- Location: Oslo, Norway

- Graduation Date: 2010, Ph.D.

- H index: 19

- Twitter followers: 385

Hello! Who are you and what are you working on?

My name is Sarah Rosenbaum, and I live in Oslo, Norway. I’m actually from the USA, but I’ve been living in Norway since the end of the ’70s. I’m a graphic designer and illustrator by training but went back to school and got a Ph.D. in 2010 from AHO (Oslo School of Architecture and Design). So now I am a researcher, with a visual communication background. I’m employed at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Centre for Informed Health Choices. I’m one of several people in a multi-disciplinary research team in this center – our aim is to support people’s use of evidence in decision-making about health interventions. I bring a user-centered/human-centered design perspective to our work.

When I first got involved in this environment, I was interested in research questions about how to best present results of research evidence (about the effects of interventions) in ways that make them easier for a broad range of people to understand and use in decision making – health professionals, policymakers, or patients and the public. My Ph.D. builds on this topic. But more recently we’ve been working on developing and evaluating learning resources that can help people better understand and think critically about this kind of information, starting with younger people.

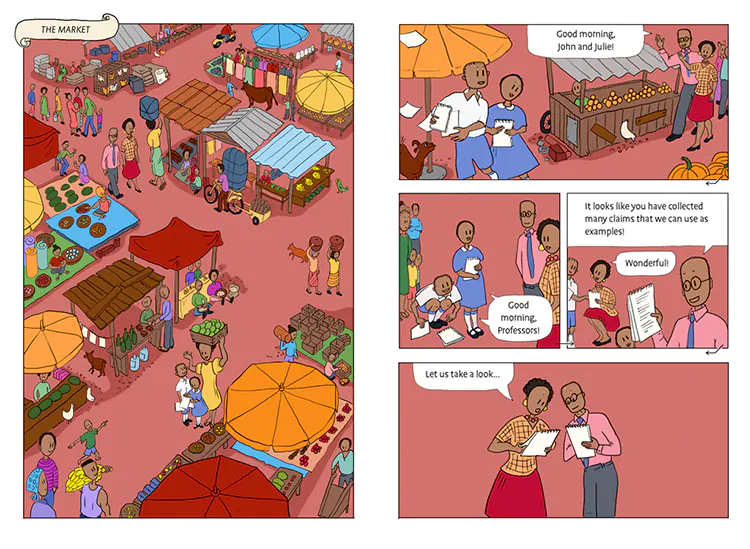

The main project I’ve been working on since 2012 is The Informed Health Choices Project. Our goal is to develop effective learning resources to help people think critically about treatments or other health interventions, and how to make informed decisions for themselves, their families, or their communities.

What’s your backstory and how did you come up with the idea?

Well, the backstory isn’t mine. The original idea is the brainchild of my colleague, research director Andy Oxman. Andy is a public health physician and health systems researcher, and he’s been studying ways of helping people to use research in decision-making for 30 years, but previously with a focus on adults.

Many years ago he was at his kids’ school, teaching about randomized trials. And he realized that the students readily grasped a lot of the basic concepts about how to test things in a fair way when you’re trying to find out whether something has an effect or not, like the need for a control group, or the need for blinding or randomization. That’s where he got the idea that this is something that we should do – teach kids these concepts instead of adults.

It seemed to him that it might be easier to teach kids about what reliable evidence in this context looks like, and how to spot bogus claims because adults have a lot of preconceived ideas that get in the way of their learning.

Based on this idea, our team submitted a research proposal to the Norwegian Research Council back in 2012, in collaboration with Iain Chalmers in the UK and a team at Makerere University in Uganda where Andy had been a guest researcher for a year, to develop and evaluate two sets of learning resources for use in East Africa – resources for mass media and resources to be used in primary schools – but that could be generic enough to also be used in other settings. We didn’t think we would get the funding – we thought it was a bit of a crazy idea. But the Research Council approved our grant for the original five-year project, and then again in 2019 for a new project aimed at secondary school students, in collaboration with research teams in Uganda, Kenya, and Rwanda, which is what we are currently working on.

A school administrator (far right) and Allen Nsangi discuss something during a pilot lesson, in Uganda. As a doctoral candidate, Allen, affiliated with Makere University and the University of Oslo, was a primary investigator in the development and evaluation of the Informed Health Choices primary school intervention. In the background, a group of children play a game that was part of the first set of prototypes. (Photo: Matt Oxman/Informed Health Choices)

Please describe the process of learning, iterating, and creating the project

We don’t just sort of get a good idea and run out and evaluate it in a trial – we spend a lot of our project time developing – getting the content and design right, and working a lot with users and other stakeholders. In a five-year project, we’ll typically spend about three years developing. Early on we conduct systematic reviews, to see what other relevant products, frameworks or strategies have been evaluated, and what we can learn from that work.

When we start to create learning resources, we use a human-centered design approach – this means we spend a lot of time understanding the context of use, engaging with stakeholders, getting ideas and feedback from teachers, students, curriculum developers, exploring user experience of our prototypes and improving them. We do a lot of iterations, both of content and format. We try to involve users – teachers and students – as much as is pragmatically possible in developing the learning resources. That can be challenging when the content is unfamiliar to them to begin with. At the very least, we can discover what they find easy or difficult, what they like or don’t like, and what might motivate them. And we learn a lot about what kind of learning resource would be suitable for use in their context.

Understanding context of use, trying out ideas early and having enough time to make mistakes is critical. Even though we work in close collaboration with partners in East Africa, we still can make wrong assumptions about what is possible or what can work in that context. For instance, when we started creating learning resources for primary school students, we had a lot of ideas that we tried out early and that didn’t work, like game-based activities that didn’t work because of the large class sizes. We made rapid prototypes, tried them out in schools, and saw they completely failed. So, we had to swing around and change our approach and our design a lot. You need to plan for time to do this kind of trying out ideas and failing. You need to build in space for this kind of testing ideas and failing already in your grant application. If you don’t have time to fail, you’ll never really be able to innovate.

When we are done with our development phase, then we evaluate the learning resources in a randomized trial. During and after the trial, we carry out a process evaluation, to better understand the results and to explore issues related to implementation and scaling up. For the primary school resources, we also did a one-year follow up trial, to test how much learning students and teachers retained over time. At the end, we create guidance for people to carry out translations and contextualize the resources and provide them with protocols for this further development of what we produced. So, you see that we use a lot of different methods, both from design and from qualitative and quantitative research, in a project like this.

I forgot to mention where the learning content came from. Before developing any learning resources, we needed to establish people need to learn in order to be able to assess a treatment claim and how to make informed choices. So, we reviewed existing checklists and frameworks and developed the Informed Health Choices Key Concepts, which is kind like a curriculum for teaching about these things. Then, together with teachers, we decide which of those Key Concepts it is possible to teach to the age group we are targeting. There are about 40 key concepts – they’re reviewed every year – but some of them are more advanced and not feasible to teach younger people. In the previous project, together with primary school teachers in Uganda, we determined that about 25 of them were possible to teach to fifth graders. Then we started developing resources in order to teach these concepts.

But what we found as we piloted learning resources was that we had to go much more slowly than what we originally thought. We couldn’t teach all 25 concepts in one semester. So one of the main adjustments we made was to continuously keep cutting content, many times, and simplifying. We ended up creating resources for primary school that teach 12 of the key concepts. In parallel, we developed an outcome measurement tool to measure people’s understanding and ability to use the key concepts.

A class uses the final version of the children’s book during the trial of the Informed Health Choices primary school intervention, in Uganda. (Photo: Daniel Semakula/Informed Health Choices)

Please tell us more about this measurement tool you’ve developed

Yeah, sure. To measure the effectiveness of the resources on learning outcomes, and to measure the ability to apply this knowledge – to make informed decisions – we developed a flexible set of multiple choice questions: the CLAIM evaluation tools. They can be used for creating tests to use in schools, as an outcome measurement in randomized trials, or in cross-sectional studies to gauge ability in a population. After we developed the primary school resources, we used questions from this tool to measure the effect of the learning resources in a large trial in Uganda, with about 10,000 10-12-year-olds, and also in a one-year follow-up trial.

How is everything going nowadays, and what are your plans for the future?

So, the current work we’re doing is creating and evaluating digital learning resources, for secondary school students. This is a continuation of the original project for primary school students, which was printed resources. We have a close collaboration with three incredible teams of researchers in East Africa: Uganda, Kenya, and Rwanda. They carry out all the stakeholder engagement, fieldwork, data collection, and the like, and anchor the project in their contexts.

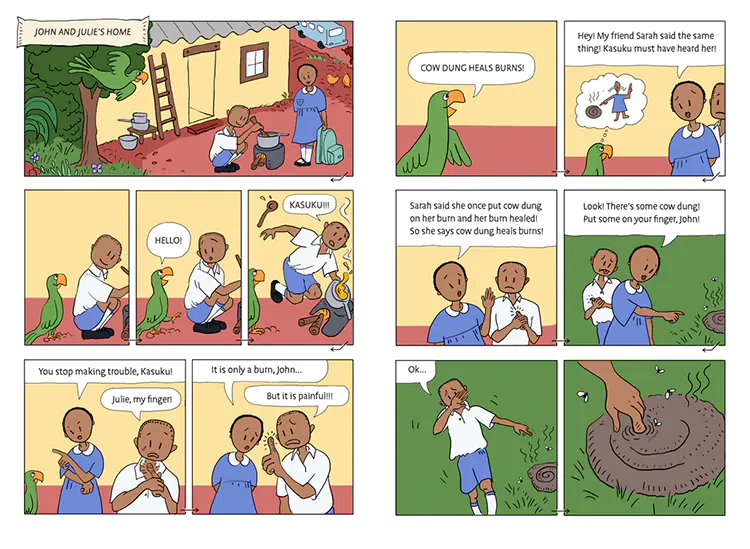

The primary school resources are available on our website. Basically, it’s a comic book, an exercise book, a teacher’s guide, and a few other materials, and these are made to be possible for a teacher to just pick up and run with it.

We made a comic book for several reasons. The first was because the content is also new for teachers, and so they needed a fairly scripted resource to be able to teach new content without a lot of prior training. Also, the comic format with images and text seems to help kids’ understanding, especially those whose English skills are not as strong. In this environment, English is used in schools, but for a lot of those kids, English is not their first language. Also, in primary schools, the classrooms are extremely large, so there isn’t much possibility to use other kinds of teaching strategies, like activities or games. We were visiting some classrooms where they were about 80 kids and one or two teachers. The kids were sitting very close together with little desk space. Teachers and students create a lot of handmade posters and learning materials that hang in the classroom. Electricity is often unstable and few primary schools have internet for use in classrooms. In that project, we thought initially we were going to create interactive learning games, but that was just completely wrong for the context.

Team photo, primary school resource project (ca.2016), with some of the partners from Uganda, Kenya, UK and Norway: Daniel Semakula, Esme Lynch, Angela Morelli, Nelson Sewankambo, Claire Glenton, Matt Oxman, Iain Chalmers, Sarah Rosenbaum, Andy Oxman, Simon Lewin, Margaret Kaseje.

So you had to take the project in a different direction, correct? Was that the main reason or something else?

Originally, the primary school resources, yeah. We thought we were going to create something digital but those resources were just not feasible to use in that kind of setting. So, it kind of forced us to sort of work toward creating a set of resources that could work in a low-resource setting. We also had to make things that were understandable for kids who didn’t have English as a first language, and for potentially very large classes. We ended up with the comic format that was highly illustrative, which the teachers and students experienced as being really helpful. Kids could read it on their own, teachers could read to the class, classes could read all together in unison. In some classes we saw kids taking turns role playing the different characters in the comic. It turned out to be a very engaging and flexible learning tool.

Another thing that changed as we progressed was our framing of what people would be learning. We began with the idea of teaching kids about the reliability of claims from research. But we realized that the concepts about the reliability of claims were applicable to all kinds of claims (about the effect of interventions). So we reframed the content of the resources to start with learning about what makes a good claim, a reliable claim. Teaching people not to judge reliability by looking at the source – who made the claim- which a lot of information literacy programs do in schools, but to ask: “What is the basis for that claim?” regardless of the source. This learning applies to claims about interventions also in other areas than health.

The Health Choices Book (2016)

Two spreads from The Health Choices book (2016)

I assume it’s a different approach involving a lot more critical thinking than usual, right?

Exactly.

We wanted to ask whether you could see a carry-on from this learning. Because this must be something you want them to keep until adulthood.

Right. Yeah. Well, let me describe some of what we learned in the last project. In parallel with working with primary school students, we were funded to do a mass media intervention, basically with the same objectives, but a different target audience.

We ended up targeting parents of primary school children and developed a parallel set of resources for them. We created a series of podcast episodes using the same human-centered design approach with lots of iterations to develop the material. Some of the parents were illiterate, so we needed to create a resource that could also reach these groups, which is how we landed on an audio resource. The underlying learning content was pretty much the same thing that the kids were learning, but a completely different format, different stories, and an audio delivery. For the trial, we made sure that people were actually listening to the podcasts – a team of research assistants each followed up with a number of participants over some weeks, and delivered two episodes of the podcast per visit using portable media players, collecting answers to the trial questionnaire at the end. So you could say it was an explanatory trial, to see if this intervention could work because we made sure participants listened, and then measured the effect of their listening on learning outcomes, rather than a pragmatic trial.

We did a one-year follow-up trial, both with the primary school students and with the parents. What we found was that the learning resources resulted in large learning effects in both trials. We were quite surprised by the results from both groups. The children and the parents learned a lot more than we expected. (You can read about these trials in the two Lancet publications – the primary school evaluation and podcast evaluation). But after one year, something interesting happened in the follow-up trials. What we saw was that more children in the intervention group had a passing score after one year, whereas the number of parents in the intervention group with a passing score decreased after a year. The parents had lost more of what they had learned. That the kids increased their knowledge after one year was very interesting. It shows that it’s a good idea to teach people these kind of concepts when they are young.

Are you currently continuing with this project?

Yes. The same funder, the Norwegian Research Council, funded a new project for us in the same program (GLOBVAC). So now we are working on digital resources for high school-aged kids. We are collaborating with the same core teams in Uganda, Kenya and Rwanda, and have a Ph.D. fellow in each of these countries.

We also have an IT developer in Chile that we’ve worked with on other projects, Epistemonikos. Because of the digital component of this project, we conducted a context analysis in each of the three countries at the beginning of this project. Where we go in and look at the context before deciding how we’re going to develop the resources. We began with an assumption that there are some computers for use in teaching and learning in high schools in these countries. But we needed to see if that was the case, and what kind and how many computers they actually had, and if they were available for students. So that was a very, very helpful step to do first.

In the Rwandan context analysis, we found that they’re rolling out IT in schools quite systematically, with internet infrastructure and local servers and wifi in schools. They have what they call a ‘smart classroom’ with 40-50 computers each in two classrooms. So far they’ve rolled this out in about half of the high schools in Rwanda. But whereas in Uganda and Kenya, the infrastructure for establishing IT infrastructure in schools is much, much less abundant and more sporadic. In all three countries, there are still many schools without any IT infrastructure or resources for students and teachers. So, it’s making us consider how we can develop and implement a digital intervention that can reach kids even where there aren’t computers or devices for them to use directly. That basically means you’re back to the teacher on a blackboard. But the question is: how does the teacher get ahold of a digital learning resource to use for teaching new content in a non-connected classroom? So we’re having to sort of rethink how we’re going to make this work…

Through your science, have you learned anything particularly helpful or advantageous?

Well, I mean, one of the things I think is really critical is working as a team and working with people from other disciplines.

I think that one of the most helpful things that I’ve been lucky to be able to do is to come into a multi-disciplinary team with people from highly varied backgrounds – health research, social science, education, etc. – but who are all pulling together towards the same kind of objectives. Yeah. That’s been really interesting. And being a designer kind of turned into a researcher, I am really aware of the value of a diversified team. Because I’m not a very typical addition to these teams, I’ve thought a lot about the value of bringing a design perspective into research. I think it has been really beneficial for our projects. Every researcher should have a designer, if you’re developing new things that you want people to use and find meaningful, anyway 🙂

What you do on a daily basis. What is your morning routine, and what does a typical day look like for you? People are interested in how a scientist works.

Oh, that’s pretty boring. This last year, I’ve been working from home. I get up and go for a walk in the morning, so that when I come back, I am at ‘work’. Lots of the people I work with are somewhere else, for instance in East Africa. We have Skype meetings once a week and then work pretty much independently all week long.

Every Tuesday, we have meetings and go through all of the items on our agenda of what things are in progress. These meetings are really structured. We always have an agenda. Somebody always takes notes, and the notes are always written up as action items with names on them. The next week we go through the action items from last week. Even when there isn’t COVID, basically most of our project communication is through Skype and follows this structure.

What kind of professional tools do you use that you would recommend?

When I’m designing or illustrating, I use the Adobe suite. I use Adobe XD to mock up prototypes of interactive things. I also use Photoshop and Illustrator when I’m designing for print or illustrating. More lately, I’ve been using an iPad and Affinity Designer to create illustrations. Our team uses the Microsoft package: Word, Excel, and Powerpoint. And we also use Google Docs. I think our team, more and more, uses Google Docs when we’re working across countries and institutes.

We also use SharePoint, which is sometimes challenging for people outside the institute to get stable access to. It’s much easier for us to use Google Docs when we have more sort of informal meetings and collaborations. And I use EndNote for managing references.

Do you have any podcasts within the design field or anything that you can recommend to readers who may have similar goals to you?

Podcasts. Well, I started listening to something called 99% Invisible, which is a radio show that focuses on design and architecture.

Besides being 99% invisible, I listen to the Rachel Maddow Show regularly. I also listen to the New York Times Daily, and Pod Save America, news-related stuff. And I also like the New Yorker, which has a fiction podcast where they ask authors to choose a short story from the archive and read it out loud.

I also listened to a weird British podcast called Desert Island Discs. It’s a radio show that turned podcast. It’s been going on for like 40 years. A British friend turned me on to it. Each week they ask a guest to choose 10 music tracks that they would bring with them if they were stranded on a desert island. It’s a really intriguing strategy for getting into somebody’s life story. Because people pick tracks that have been meaningful to them, starting from when they are young until they are older, and talk about why. Basically, you get somebody’s life story as they are reminiscing and reflecting on the music they care about. It’s really cool and very interesting.

What other kinds of things do you do in your personal life? Cook? Self-care? Hobbies?

Well, I’ve started oil painting in the last couple of years. I need to have something to do when I retire 🙂

I’m a designer and an illustrator, so I’ve always worked visually. I like moving between creative work and more logical, rational work. It wasn’t really given that I was going to become a researcher, but I couldn’t ever have envisioned just doing only visual work. I like making useful things, which is why I got into design. But I like using other parts of my brain. When I have free time, I like to leave the rational side behind.

Earlier design work (1992): Pictograms, Olympic Games Lillehammer ´94

Painting (2021)

What advice would you give to other researchers? You have a very unique position, but I can imagine there are others out there who are designers and may have a foot into science. What kind of advice would you give to them starting out?

I was telling my daughter that I was going to do this interview, and she said, “Oh, that’s good because then other people will learn that they can make changes mid-career as well.” And I guess that’s what I did. I mean, I was a designer until… I mean, I still am a designer. But I have started a few companies, and I had a successful design career until I was in my late 40s. Then I started a Ph.D. and completely switched. I sold my stock in the company where I was a partner and started working for an institute that now is a part of the Institute of Public Health.

So yeah, I mean, I think you just need to follow your own interests and your own path, and not worry too much. And I say that sort of tentatively, because that used to be the case when I was young, that was the advice, to just follow your passion and do what you’re interested in, and things will come to you.

I’m not really sure the world is kind of like that anymore. But that’s still – from somebody in my generation- the advice that I would give to people is to do what you’re interested in and not what you think will be good for your career because then your career will come to you. A lot of the interesting future jobs don’t even exist yet, so how can you strategically plan for them?

It’s a great example of how you don’t have to be scared of moving from fields. People have always thought we have to stay in that same field for the rest of our life. And if you leave, it’s a scary process.

I don’t really know the American market well enough to say this, but I know that in Norway, it’s been relatively easy for me. I’ve always experienced it as fairly easy to be a sort of generalist, somebody with many skills. I’ve always heard that you really had to specialize – if you were going to illustrate, you had to really go down one path, and you had to have a particular style, and everybody had to know what that was. But I never really had one way of doing things. I was always more interested in the problem, or the project at hand, and what kind of approach that suggested or demanded. And then I would adapt what I did to that rather than having one way of approaching everything visually. We approach our research work that way too – what is the problem we are interested in – that is the main issue. Then we figure out what is the best research method for exploring that question.

One thing I would encourage younger researchers to think about is who will use their research and how they can more actively engage with those people. Traditionally, a lot of researchers write for other researchers. Maybe in some fields, that’s fine, because it’s only your peers who will be using your work. But in a lot of research, there are other people that might be using your research. That’s kind of the core of what I’m interested in, is getting research into practice or into use. I think that’s important. If researchers are interested in that, they need to understand who their users are, what their needs are, and to learn that, they need to engage with them.

In health research, this has become much, much more common. Funders even ask for how you’re going to engage with your target population when you are applying. It’s important to bring people on board early so that you don’t decide everything first – for instance not deciding on all your outcomes before you’ve actually asked people if these are outcomes they’re even interested in. That is a good role for designers in research, because many designers, especially the younger ones, have experience with participatory or co-design processes, and seeing things from the user perspective. Researchers could learn a lot from the field of design.

Certainly now, this last year has really highlighted the importance of this kind of work. We would love to see this sort of thing rolled out worldwide. Not just in East Africa.

I forgot to talk about that. So, we created these Informed Health Choices learning resources, they’re on our website, they’re free, and they’re open access. We’ve also created a set of guides for people to translate and pilot resources in other languages and settings, and so far, there are a lot of people doing that. We have an informal network of people involved in translation or contextualization and publish a newsletter annually that describes who is doing what in different countries. On our website, there’s also a language menu at the top where we have access to finished translated resources in several other languages, including Spanish, French, Norwegian, Swahili, etc. Teams in several places, such as China, Iran, Brazil, and other countries are working on translations that aren’t finished yet.

We’ve tried to facilitate spreading into other languages and settings by developing guides to help people carry out translations. The podcast has also been replicated for other settings: a researcher in Florida developed a version of the podcast for American adults. So people have sort of taken the basic sort of skeleton of the work and recontextualized it. All of those things are available on our website.

Thank you very much for your time, Sarah. Where can we go to learn more?

› Informed Health Choices:

https://thatsaclaim.org/

(IHC Key Concepts, for health and several other fields)

› Personal:

Interview about design work from 2016 (in Norwegian but with images)