When we hear the term “renewable resource”, we think of solar, wind, and water energy, not biomass (or in this example: fish). The fishing industry is perhaps one of the biggest and most widespread industries known to man and often enters the mainstream media in a poor light, especially in regards to overfishing. We don’t hear how, if managed sustainably, fish can be a renewable and indefinitely accessed resource. Currently, it is estimated that one billion people in coastal regions, mainly in developing countries, rely on fish as their primary source of protein [1] and so this should surely be a major topic of conversation. As well as researching across multiple sources in this investigation I interviewed Professor Carlos Garcia de Leaniz from Swansea University, whose input shall be included to help us understand this complex situation.

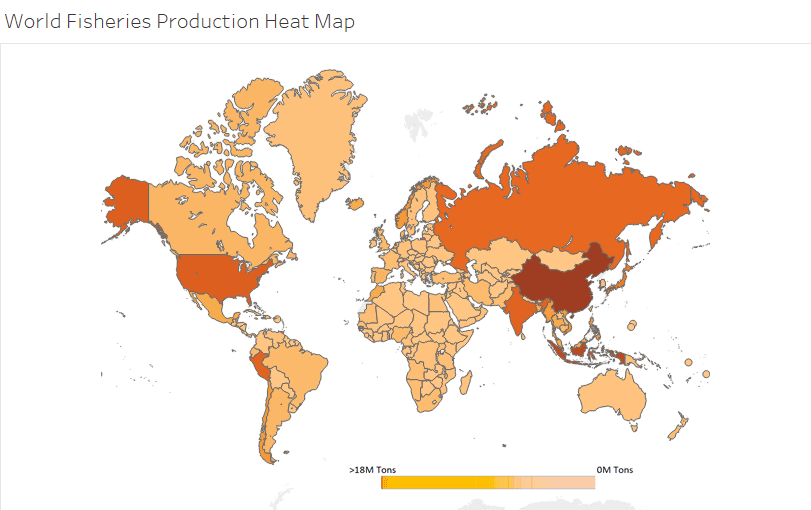

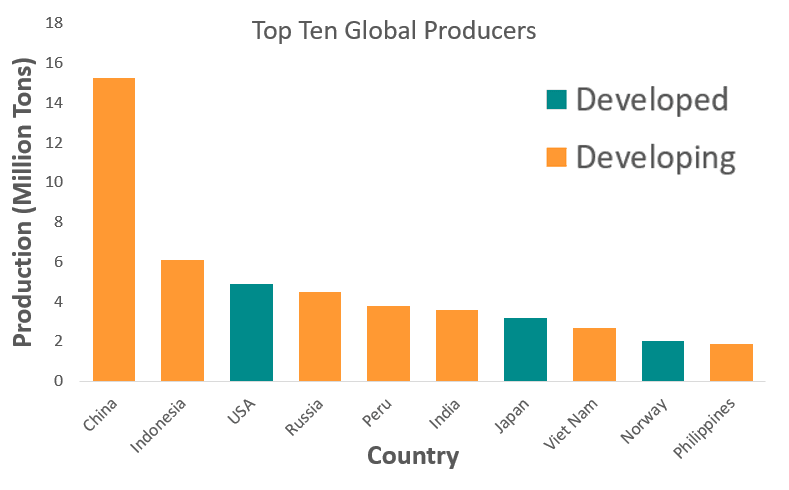

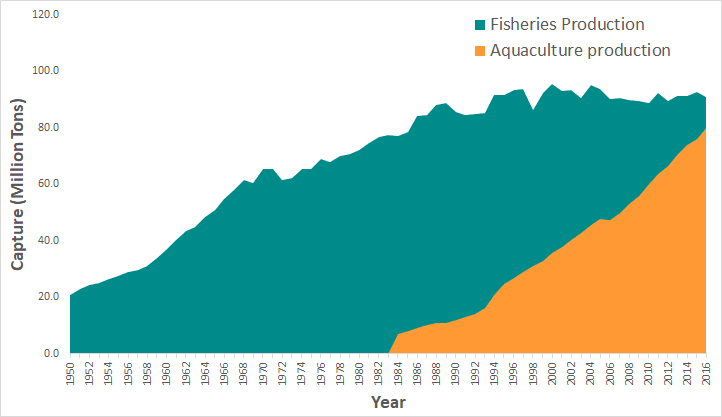

According to the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), from 1961 to 2015 the global fish consumption outpaced population growth and accounts for 17% of all animal protein consumed [1]. Global fisheries catch rapidly increased from the ‘50s to ‘90s and but has since plateaued. This because of the increased action of more sustainable and restrained fishing taking place due to the recognition of the damage being done. Along with this, the aquaculture industry has grown massively, offering an alternative where fish can be grown in a completely or relatively controlled environment designed to maximize growth and profit.

In 2015, 30% of fish stocks were overfished and 60% were fished at their maximum sustainable limit [1], with this being some of the most recent data released by the FAO, now being in 2019 we can assume with previous trends that this has worsened. So, what exactly is overfishing? Professor Garcia de Leaniz explained:

“[Overfishing is] taking more fish than a stock can naturally replenish through recruitment. There are 2 types of overfishing:

Growth overfishing [is when] fish [are] caught at too young an age. So, fishermen do not benefit from the period of maximum growth. [This causes a] decreasing yield with increasing fishing effort as a result of decreasing average size of fish in the catch.

Recruitment overfishing [is when] too many adults are removed from a stock so there is an insufficient number of mature fish (spawning biomass) to maintain levels of recruitment [resulting in] poor year classes.”

I asked Professor Garcia de Leaniz to explain why overfishing is such an important issue for humans and the environment: “Overfishing is the number one reason for fisheries declines and 90% of fish stocks are now overfished or fully fished. Fish are important for humans for: 1- Food Security (More than 4.3 billion people rely on fish for animal protein), 2 – Economic growth (More than 55 million jobs depend on it) and 3 – Health (OMEGA-3 PUFA fatty are essential dietary requirements fish are the main source of them).”

So why do fishermen not seek out long term objectives both for their industries and for global food production? The ‘tragedy of the commons’ (TOC) is the answer to this dilemma [2], the term first coined by Garrett Hardin in 1968, Professor Garcia de Leaniz enlightened us to exactly what this means:

“Fisheries harvest a renewable resource and can therefore provide a continuing valuable production BUT the raw material, the fish, is not owned by any one extractor (nor even any one country). This is important where stocks cross national boundaries (mixed stock fisheries). When people exploit a common resource (such as a fishery), competition between users will often lead to overexploitation as the costs and consequences of overexploiting are shared by many people while the benefits are enjoyed only by those who overexploit. There is thus an asymmetry. So individual fishermen cannot husband their resource, ie show restraint; that just makes more available for their competitors. This results in competition, where each fisherman harvest as much as they can today (short term) without regard to the future (which needs long term planning). That’s why stocks need to be regulated and fishing cannot be left to the individual fisherman. It must be governed at local, national & international scales.”

As Professor Garcia de Leaniz explained fishing must be governed at these higher levels and often governments implement regulations to try and prevent the tragedy of the commons from happening, but in reality, they often exacerbate it [3]. For example, minimum legal sizes are a common restriction used to try and combat growth overfishing. Allendorf [4], showed that minimum legal sizes caused a population of Rock lobsters (Jasus edwardsii) to decline in size from the 1970s to early 2000s. This is because only the smaller lobsters remain to reproduce causing the population to acquire these traits. Professor Garcia de Leaniz was able to tell me why these restrictions rarely have the desired effect: “Because fishing cannot be regulated based solely on biological data (the fish). The social angle is equally important, but this is often more intractable than the biological challenges (stock-assessment)”.

To discover this, we need to calculate the abundance of fish stock, a stock being a self-contained population where the losses and gains by migration are negligible compared to growth and mortality. Bioeconomic models are used to calculate the abundance of a stock and then to estimate its maximum sustainable yield (MSY). The MSY is the highest rate at which it can be exploited without long-term depletion. This means preventing three factors: do not catch too many fish, do not catch fish below a certain age, and do not remove all the large fish from a stock. The MSY however is often over-calculated, leading to over-intensive fishing practices.

Developing countries do not always have the infrastructure, resources, or manpower to make legislations and enforce them. Small-scale fisheries, struggling to keep up with the coastal population growth, account for the majority of the world’s fishers and are dominantly within developing regions. The policymakers here face tough decisions where they must preserve the environment but also the livelihoods of the people who depend on them. Research suggests that stocks in these regions are declining to such low levels that they could be past recovery before long [5]. A ‘hit the brake’ method is often enforced in small-scale fisheries, when stocks are near their limit they stop and wait for them to recover before starting the process again. This is not a sustainable method of fishing and scientists are being encouraged to work with these fisheries to impose sustainable limitations and practices [5].

The biggest problem regarding overfishing is the illegal, unregulated and unreported (IUU) fishing activities that occur around the world. These are activities where fishing violates restrictions, targets restricted species or mis-reports catch in order to gain more profit. I asked Professor Garcia de Leaniz why this was such an issue: “It is difficult to take [IUU fishing] into account and management plans, and [it] defies regulation. It is the best example of TOC”.

This obviously has devastating effects on calculating the bioeconomic models trying to calculate MSY and fishing efforts and is a fast route to stock collapse. IUU fishing accounts for around 15% of the global catch with an estimated worth of €10 billion ($11.2 billion) [6], this is a massive number both in terms of biomass and economics. It’s been shown that increased IUU fishing occurs when commercially significant species occupy area’s near ports of convenience and is also driven by the demand for ‘delicacies’ from around the globe. China almost single handedly drives the global shark fishing industry [7].

Global fisheries production is projected to increase [1], thus the world is in dire need of effective solutions that preserve both the environment and people who live with it.

It is not clear whether the industry is changing [8], yet we can make producers more accountable by taking a wholistic view of the process. The Marine Stewardship Council (MSC), founded in 1997, is a non-profit organization that awards seafood products with a certificate of sustainability if the food can be tracked back to an MSC certified fishery. This while a great idea is not the perfect solution and in many developing countries it has reduced the income from fisheries [9]. Other organizations, such as Our Oceans, have succeeded in securing mass funding from ocean stakeholders which they have used to secure marine protected areas [6] and promoting maritime security, sustainable fisheries, pollution and climate change.

Evidence shows that the recovery of fish stocks takes far longer than initially thought [10], fisheries that declined in the early to mid-1990s are now only just recovering, 20 years later. Stocks that recover quickly however occur with species that mature early in life and are fished with highly selective equipment [10]. This shows the need to be very specific when we are catching our target species. With proper management techniques, good environmental equipment and a thought for the long-term process rather than short term gain we can turn this around and make fishing a very sustainable process.

Professor Garcia de Leaniz had this to say about what we can expect to see over the next 20 years in regard to overfishing and fish stocks: “Wild stocks will likely decline or remain stagnant. Aquaculture will continue to grow. At the current rate of growth, most fish we eat will be farmed by 2025. Both the fishing and aquaculture industry should become more sustainable. Consumer pressure for sustainability will increase”. As such we must consider how important the aquaculture industry is to preventing overfishing: “Aquaculture has contributed in some cases to aggravate the problems of overfishing by relying on fish oils to feed carnivorous fish, but the aquafeeds are increasingly being made more sustainable. [Over] 50% of all the fish we consume already come from aquaculture, and it is the only long-term solution to feed an increasing human population.”

A world hunger crisis is on the horizon if not already present for many countries and ensuring sustainable indefinite fishing with minimal impact on the environment is one source of prevention. Ultimately, we are part of this environment, we may not be in the ocean but many communities, towns and cities all over the world depend on it for economic stability. It is in our own interest to preserve fishing in a sustainable manner if we have any hope to sustain ourselves.

My final question for Professor Garcia de Leaniz was asking him whether he believed that humans will be able to manage fisheries sustainably and that as a planet will we realize soon enough to make this a reality? His response summed it up perfectly: “Yes, we have no choice”, adding: “I always tell my students – Do something cool with your lives – work on fish conservation”.

[1] – FAO. (2018). The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2018. Food and Agricultural Organisation. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/3/i9540en/I9540EN.pdf

[2] – Hardin, G. (1968). The Tragedy of the Commons. Science1, 162, 1243–1248.

[3] – Benjamin, D. (2001). Fisheries are Classic Example of the “Tragedy of the Commons.” PERC, 19(1).

[4] – Allendorf, F., England, P., Luikart, G., Ritchie, P., & Ryman, N. (2008). Genetic Effects of Harvest on Wild Animal Populations. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 23(6), 327–337.

[5] – Purcell, S., & Pomeroy, R. (2015). Driving small-scale fisheries in developing countries. Frontiers in Marine Science, 2, 44.

[6] – Ocean, O. (2018). Our Ocean Conference 2018. In Sustainable Fisheries.

[7] – Petrossian, G. (2015). Preventing Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) Fishing: A Situational Approach. Biological Conservation, 189, 39–48.

[8] – Iles, A. (2007). Making the Seafood Industry More Sustainable: Creating Production Chain Transparency and Accountability. Journal of Cleaner Production, 15, 577–589.

[9] – Ponte, S. (2012). The Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) and the Making of a Market for “Sustainable Fish.” Journal of Agrarian Change, 12, 2–3.

[10] – Hutchings, J. (2000). Collapse and Recovery of Marine Fishes. Nature, 406, 882–885.