Learned helplessness is a psychological phenomenon that occurs when an individual is repeatedly subjected to an aversive stimulus that they cannot escape or avoid. Over time, the individual learns to believe that they have no control over their situation, even when opportunities to escape or avoid the aversive stimulus become available. This concept was first identified by psychologists Martin Seligman and Steven Maier in the late 1960s through their experiments with dogs. They found that dogs subjected to inescapable shocks eventually stopped trying to avoid them, even when escape was possible, demonstrating a sense of helplessness [1].

The theory of learned helplessness has been extensively studied and linked to depression in humans. Depression is a common and debilitating mental health disorder characterized by persistent feelings of sadness, hopelessness, and a lack of interest or pleasure in activities. The connection between learned helplessness and depression lies in the perceived lack of control and the expectation of future failure or suffering, which can lead to depressive symptoms.

Animal models play a vital role in researching the causes and effects of depression and the efficacy of antidepressant drugs. One such model is the learned helplessness paradigm.

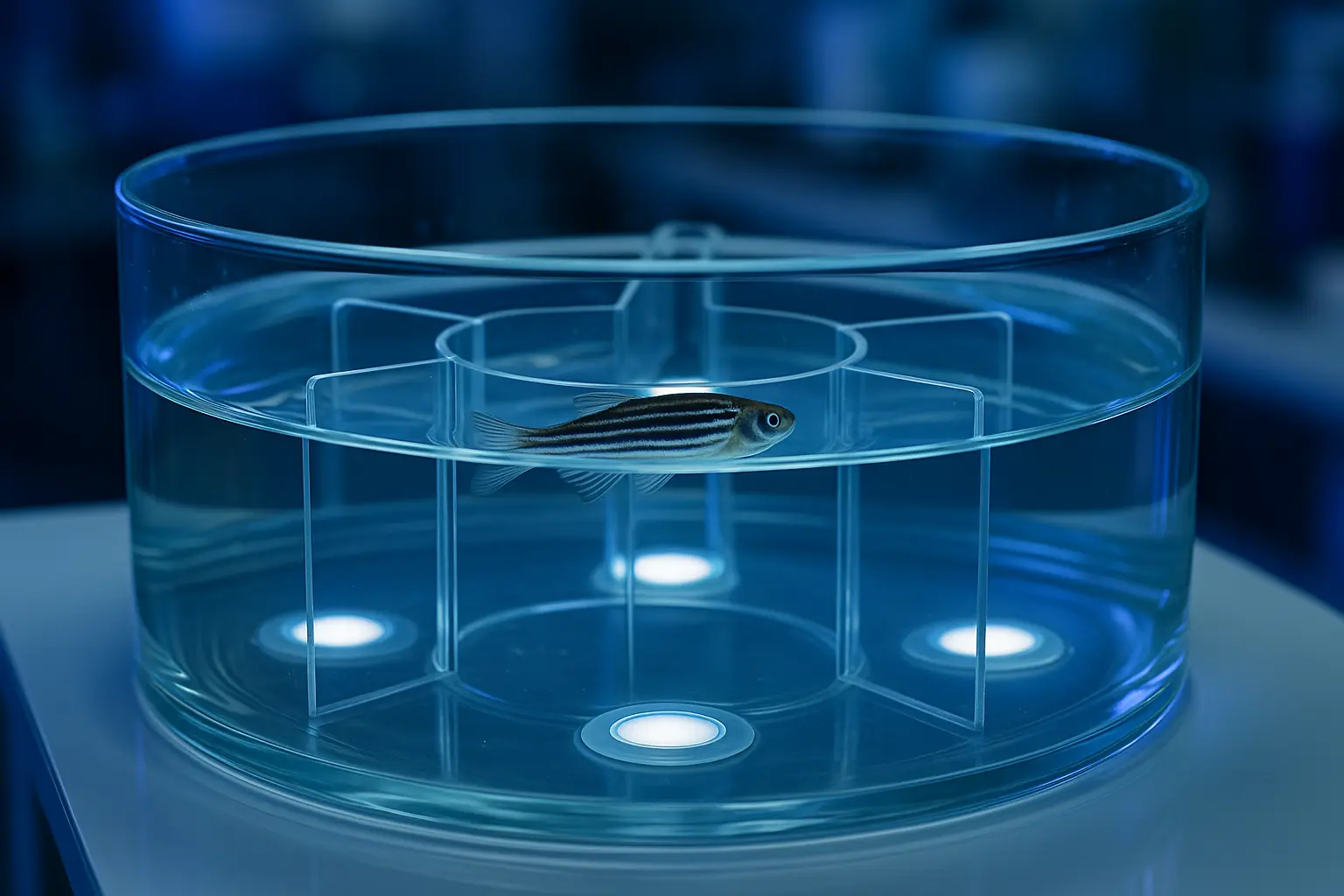

The equipment used to induce learned helplessness includes a shock generator. The animal is placed in a box-shaped chamber with a floor made of steel rods to conduct the shocks. Additionally, the chamber has an escape method, often a second chamber, allowing the animal to physically escape the shocks.

The protocol comprises three phases: induction of depressive-like symptoms, recovery, and testing. In the induction phase, animals are exposed to a shock procedure for a set number of days. Only control animals have access to an escape method during this phase, while the learned helplessness group does not. The shocks are randomized to mimic chronic symptoms, with sessions typically lasting 45 minutes to an hour, depending on the laboratory and the specific effects being tested. After the induction phase, animals undergo a 24-hour recovery period.

In the test phase, the escape method is installed in the chamber for both control and experimental animals, and they are subjected to shocks again. The control group, having learned to press the lever or escape into the no-shock chamber, will actively avoid the shocks. In contrast, the experimental group, conditioned to believe they cannot escape, will accept the shocks despite the presence of an escape method.

This paradigm effectively demonstrates the concept of learned helplessness, providing valuable insights into the mechanisms underlying depression.

The learned helplessness model has provided valuable insights into the cognitive and emotional processes underlying depression. It demonstrates how exposure to uncontrollable stress can lead to a state of passive resignation and a pervasive sense of powerlessness, mirroring the symptoms of depression in humans [2].

During the test phase of the learned helplessness paradigm, researchers measure escape latency, which is the time it takes for an animal to escape from the aversive shocks. Animals in the learned helplessness group typically show significantly higher escape latency compared to control animals, reflecting their learned sense of powerlessness.

One significant advantage of this test is its ability to assess the efficacy of antidepressants and other treatments for depression. For instance, fluoxetine, a Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI) known as Prozac and Sarafem, has been shown to reduce depressive-like symptoms in animals subjected to the learned helplessness paradigm [3]. Effective antidepressants should decrease the latency to escape, indicating an improvement in the animals’ coping behaviors.

Although there is ongoing debate about the precise role of serotonin in depression, the effects of SSRIs in both learned helplessness studies and human treatments suggest that these medications can reduce depressive symptoms. This supports the notion that SSRIs enhance mood and motivation by altering neurochemical pathways linked to depression.

By examining metrics such as escape latency, researchers gain insights into the behavioral and pharmacological factors that influence depressive states, contributing to the development of more effective treatments.

There are numerous rodent models used to study depression, including the forced swim test and the tail suspension test. But what distinguishes these tests from each other?

In the forced swim test, mice are placed in an inescapable tank filled with water. Mice exhibiting learned helplessness will remain largely immobile, only making minimal efforts to stay afloat [4]. In the tail suspension test, mice are suspended by their tails from a clamp, preventing them from reaching any surface. Eventually, they stop struggling and hang immobile.

The learned helplessness test is considered more sensitive to a wider range of antidepressant drugs compared to the forced swim test [5]. However, the validity of the tail suspension test as a model for depression has been questioned, as it is unclear whether the observed immobility genuinely reflects depressive behavior [6].

Despite these tests’ usefulness, they all have limitations. One significant drawback of the learned helplessness model, as well as the tail suspension test, is that the depressive effects are relatively short-lived. The sense of helplessness diminishes not long after the shock protocol ends. Additionally, variability in protocols and mouse strains across different laboratories can lead to inconsistent results.

Nonetheless, the learned helplessness test remains one of the most widely used models for studying depression and evaluating potential antidepressants. As the focus on developing effective treatments for depression intensifies, this model continues to be a crucial tool in the field of depression research.

The learned helplessness paradigm not only provides a valuable model for understanding the mechanisms underlying depression but also serves as an important tool for testing the effectiveness of antidepressant therapies. By examining metrics such as escape latency, researchers can gain insights into the behavioral and pharmacological factors that influence depressive states, ultimately contributing to the development of more effective treatments.

Vanja works as the Social Media and Academic Program Manager at Conduct Science. With a Bachelor's degree in Molecular Biology and Physiology and a Master's degree in Human Molecular Biology, Vanja is dedicated to sharing scientific knowledge on social media platforms. Additionally, Vanja provides direct support to the editorial board at Conduct Science Academic Publishing House.