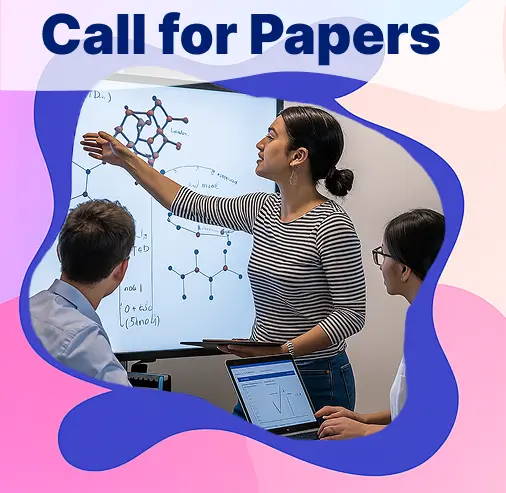

For every grant application for the National Institute of Health (NIH) funding award program, there are several review panels consisting of a group of reviewers with different expertise areas and experience. Grant application reviewers are often regarded as an academic power group. All the hardship and struggle that every applicant goes through is mostly to get past the stage of the peer-review process. Because it is quite literally the making or breaking point of every applicant’s career, be it a junior investigator or established scientist. Nobody wants to be rejected by the review committee that assesses and evaluates the application through various prisms of criteria, such as merit and proposal’s plausibility for the further progress of scientific innovations in health-related areas. (Abdoul et al., 2012)

The pressure that applicants feel upon writing and submitting a grant application for fund support is also shared by the members of any review panel because they look at the task as being a huge responsibility, given that it holds power over many of the applicants’ research careers by deciding who will be rejected the opportunity and who will be accepted to get the support to fund their research. The great number of applications that the review committee receives makes it even more difficult for the applicant knowing the level of competition to get funded he or she is faced with, as well as for the reviewers because they have to be at their absolute fair and just. It always a good idea to go through the digital archives of applications that were succeeded in obtaining federal funding, doing so can help you a lot especially if your proposal design and area have some similarities with them. (Berg et al., 2007)

Outlining your project details as elaborately as possible and sticking to every instruction is the right way to go about it. The 25 to 33 percent average success ratio of funded grants only goes to show the stiff competition and adds another aspect onto your list of things to get familiarized with before undertaking the application process, it is, to know your reviewer and the panel’s modus operandi. To enhance your chances of successful application submission for federal support, this article has compiled some essential factors from the perspective of review committee members about what they (reviewers) actually want to see in your grant application and what leads them to give positive or negative feedback, besides the NIH’ guidelines and research subjects.

Let us first understand the system; the scientific review officer (SRO) of the NIH constitutes and organizes the review panels, these panels usually involve a number of highly experienced and successful federal/non-federal scientists from academia in different roles. Review panels conduct many sessions to have multiple inputs, votes, and scoring polls in order to reach a consensus over the individual reviews done by a primary and secondary reviewer of the assigned proposals.

A small group called Lead Reviewers of highly sought-after researchers reserve the veto power that can overrule the initial review at the slightest misconduct on the part of the panel staff. To keep the integrity and structure of these sessions intact, the one member of the review committee given the role of the Program Chair, drives and moderates the discussions during and after he or she declares the final score that the proposals manage to achieve. The chairperson does not participate in voting or scoring procedures.

To understand it better still, watch the mock review panel video released by the Center for Scientific Review (CSR) at the NIH to give new applicants an idea of how the peer review system operates.

Review panelists spend long hours and great deliberation going through their assigned grant proposals according to their respective areas of expertise. The distribution of huge funds that the NIH institutes and centers (ICs) invests in research every year is a responsibility of profound consequences that grant reviewers work hard to do justice to. More often than not, the reviewers’ motivation behind taking up this strenuous task is not monetary but to enhance the credibility of the peer-review process at the NIH and to contribute to the scientific community from the position to make a difference.

The assigned reviewer to your grant proposal expects to have six major points established the first time they skim through the material your application provides.

It is basically down to these six critical factors that decide whether or not your application would make it to the review panel for a follow-up process. Each reviewer is assigned roughly 50 to 100 proposals at a time to write an individual critiqued or favored review before submitting it to the panel for further deliberation. If your grant application fails to outstand among 100s of other proposals due to the lapse of any one of these factors, your chance to score well by the panel becomes dangerously slim. So, let us go through the standards reviewers employ to establish their six points. (Arthurs, 2014).

Impactful First Impression

In an impactful first impression, the reviewer expects to learn the objective of your proposal that is described in clear and concise writing along with sufficient data that manage to project the potential of your idea and its contribution to the relevant field, as well as determine your own capabilities of conducting and sustaining the research through the research plan you provide in your grant application.

Good Proposal

The characteristics that the reviewer attributes to the good proposal are also depended on the aspects contributing to the first impression of the grant application. The well-organized, communicative, and self-explanatory project documents are considered as good proposals. Your application material should be able to explain your objective, your approach, and your commitment to achieve that objective, and your field knowledge revealed by your plan in accordance with the budget. If your project proposal manages to captivate the reviewer’s attention and interest through insightful initial data, your grant will get its first approval on the grounds of a good proposal.

Common Mistakes

When a reviewer set about going through your proposal, they have predetermined standards of evaluating the text for common errors. The gravest mistake you can make is assuming your reviewer to be an expert in your proposed field and coming across as vague through the style of writing, unnecessary jargon, formatting, misspelling, and wrong grammar. If you can’t make your case properly, why would the reviewer take it seriously? Reviewers look for clarity and conviction supported by evident competence, any proposal failing to covey gets discarded with no thought given.

Realistic Goals

The people comprising the peer review panels and committees are called the academic power group for another reason too. All of them have multiple years of experience and 8 to 10 successful grant applications making a collective worth of substantial amount. When they come across a project promising proverbial moon and stars, they reject it at first glance. Proposals that are too ambitious and far-fetching in their reach and give the impression of overestimation or impracticality hurt your chances as well as credibility like nothing else. Be as reasonable and realistic as possible because if you do get the grant, you will be legally bound to deliver upon your every word.

Budget Orientation

The Comprehensive Budget Guide that the NIH provided to align your funding requests is perhaps the only section of the grant application process that which both the reviewer and the applicant give equal proportions of check and time to. One look at the relevant section can determine if your proposal is slacking, meeting, or overpassing the particular budget requirements and hence, gets rejected or accepted. Develop and plan your project in absolute compliance with preset funding allocations in order to save both the parties’ time and trouble.

Existing Resources

The sixth factor that the reviewer employs to evaluate your proposal’s feasibility is the availability of your research resources in terms of program director’s or principal investigator’s (PD/PI) qualification and your institution’s support. Make sure to sufficiently demonstrate your existing resources by listing down equipment, laboratory space, or any of the research related possession your inventory consists of.

In the end, it is always a good idea to have another person look at your grant application proposal well advanced in time for a submission. We often miss the most obvious errors or shortcomings because of the time we spent looking at the same document. Evaluate your proposal from a reviewer’s point of view, ask all the possible questions until you can exclaim big affirmation to each one of them. Imagine your proposal being subjected to not one but many experts; this will help dissuade the myopic approach some of the successful grant writers specifically warn about. (Barrett et al., 2017).

While the peer review system cannot be challenged on the grounds of objectivity, diversity, or even self-determination with which research community paves its own future course, there are areas for which both the reviewers and PIs endorse the need for basic restructuring. First is the great power of veto in the hands of the very few to decide the bloom or doom of any proposal on the basis of a personal point of view. Another unresolved area is the consistent conflict between interactive panel review process and mail review process that divides the individuals among both the reviewers and PIs on the basis of the pros and cons of each system. Another area is referred to as the fierce competition of grant application which then results in reviewers opting for mere technicalities instead of the proposal’s merit. This only serves to aggravate the hostility some PIs feel towards the whole process of peer review, as was evident in the Sydney Brenner Case.

Monday – Friday

9 AM – 5 PM EST

DISCLAIMER: ConductScience and affiliate products are NOT designed for human consumption, testing, or clinical utilization. They are designed for pre-clinical utilization only. Customers purchasing apparatus for the purposes of scientific research or veterinary care affirm adherence to applicable regulatory bodies for the country in which their research or care is conducted.