Patch tests are one of the popular diagnostic tools used in clinical labs to investigate allergies.[1] Its main application includes the diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis (a delayed type of hypersensitivity – type IV reaction).

The test was introduced in the late 19th century, preceded by some preliminary experiments.[1] However, with technological advancements, the technique is now standardized for many allergens, concentrations, vehicles, and scoring test reactions.[1]

To verify the diagnosis, patients with allergies or contact dermatitis are reexposed to suspected allergens under controlled conditions. It’s most suitable for testing patients with arm, hand, leg, and face eczema; atopic, dermatitis, seborrhoeic, and nummular eczema; and patients with vulval disorders, chronic psoriasis, or drug reactions.[1]

Many patch tests involve chemicals present in a wide range of materials, such as lanolin, formaldehyde, leather, hair dyes, pharmaceutical items, drink, preservatives, and other additives.[2] The test is mainly helpful in cases where blood tests or skin prick testing do not work.

Further, visual patch testing evaluates the safety of preparations and chemicals that contact the skin to manufacture products based on regulatory compliance. The technique is widely helpful in recommending alternative solutions to certain medications, cosmetics, gloves, or skincare products.

Visual patch testing depends on the principle of type IV (or delayed type) hypersensitivity reaction because it takes days for symptoms to develop.[3]

When our skin is exposed to an allergen, the Langerhans cells or antigen-presenting cells (APCs) engulf the substance and break it down into smaller pieces. These pieces are then presented to Major Histocompatibility Complex type two (MHC-II) molecules bound to the cell surface.[2]

Then, the APC cells move to the lymph node and present the allergen or piece of engulfed substance to a CD4+ T-cell or T-helper cell.[2] The T-cells undergo clonal expansion, with some traveling back to antigen exposure sites.

So, when the skin is exposed to the antigen again, the memory T cells recognize it and produce cytokines (chemical signals), which trigger the migration of new T cells. This initiates a cascade of immune reactions, causing symptoms like itching, inflammation, and rash in a small area.[2]

The results from patch tests depend on several factors, including test material, system, functional and biological status of the test person, conditions in which the test is done, and the dermatologist performing the test.[4]

The test reading is done on days 3, 4, and 7,[5] and results are interpreted based on the visuals.

For example:

Result interpretation is most difficult as false-positive reactions can also occur when there are no true allergic reactions. The causes can be:[6]

Patch test systems are of two types: the original that requires allergens, tapes, and patches, and ready-to-use systems that only require removing the covering material.[1]

This system consists of four essential components:[1]

The allergen involved in patch tests should be pure and chemically defined. The test preparation comes in a bottle of inert materials and a plastic syringe to prevent their degradation or any chemical changes due to environmental factors, such as light, air, and humidity.[1]

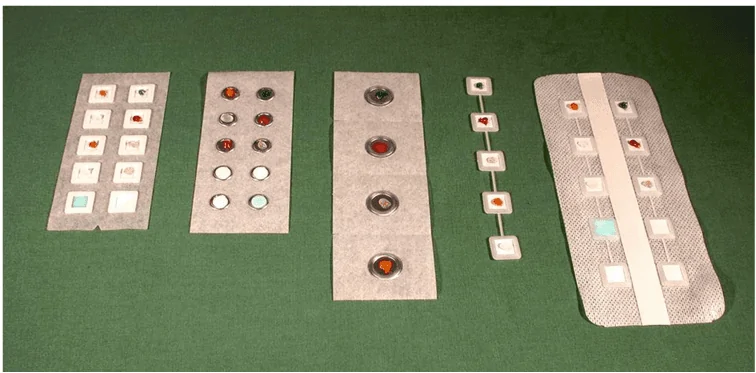

Different kinds of patch chambers are available for different purposes. In some, the test areas are circular, which is most suitable for allergic reactions, while in others, it’s 10 mm square, which is preferred to distinguish irritants from an allergic reaction. Further, these patches also differ based on their sizes.[1] For example, larger chambers are for detecting weak sensitization to contact allergens.

Figure: Different types of Patch chambers used in Visual Patch Testing.[7]

Vehicles carry allergens, and there are different types based on the type of allergen – one is not optimal for all allergens. Petrolatum is the most commonly used vehicle, as it’s inexpensive and stabilizes the allergen.[1]

However, the reliability of the vehicle becomes the question. Liquid vehicles, such as water and organic solvents (ethanol, acetone, and methyl ethyl ketone) are better for skin penetration. The drawback is that the solvents do not favor the exact dose as they evaporate.[1]

Thus, they are mainly used in research projects or to test the materials brought by patients. Some other vehicles are anionic detergents, salicylic acid, dimethyl sulfoxide, and DMSO.[7]

They are high-adhesive moisture-resistant covers used to secure the patch test in place. Examples include colophony-based and acrylate-based adhesive tapes (such as Scanpor).[1] Use reinforcing tapes if loss of the patch is expected due to sweating or high humidity.

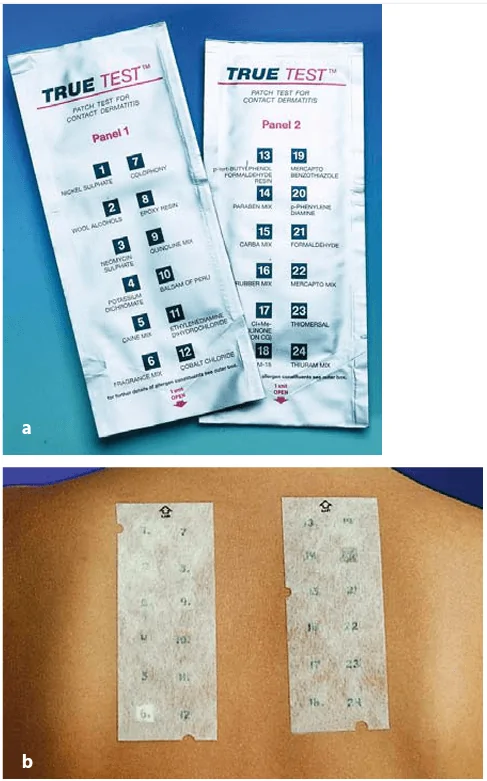

In this system, all necessary materials are prepared in advance and the doctor or researcher only needs to peel off the covering material, apply the test strips, and mark the location. In such systems, patches are generally 9 mm square and allergens are incorporated in hydrophilic gels.[1] The test is simple, reliable, and quick to perform.

Figure: (a) Ready-to-use test package; and (b) Ready-to-use Patch test on the back of the patient.[7]

Visual patch testing is a commonly used method to diagnose people with contact allergies. It’s also for testing the production of certain cosmetic and skin care products under compliance. During the test, patients are reexposed to different types of allergens in a small area of their body under controlled conditions. The testing is of two types based on easiness: allergen-patch-tape and ready-to-use systems.

The advantage of visual patch testing is that it’s easier, cheaper, and quicker, and it also offers a reliable and accurate diagnosis of contact allergies like dermatitis. However, there’s a risk of false-positive results, mainly occurring if two allergies (kept adjacent and close to each other) initiate a unique reaction.

Check out our high-quality visual patching chambers now if you need one that produces reliable and precise results!